In typical American holiday fashion, the past week was a marathon of media ingestion: a movie (Moonlight), a National Gallery art show (Stuart Davis In Full Swing), a novel (Jack Kerouac’s Dharma Bums), and an autobiography (Richard Wright’s Black Boy). It was a fun Thanksgiving, truly. Despite these seemingly random art forms and compositions, they all belonged together; they all felt relevant; and they all felt distinctly American. Why? It is strange and surprising, that these works fit together at all. And what does it even mean for something to feel “distinctly American,” anyway?

I imagine many of us are chewing on questions like this as our country faces a crisis in identity. Because that’s what’s happening, I think – no one seems to know who we are, or what the heck America stands for. Freedom and liberty and justice feel a little out the door given our incumbent President, our incarceration system, our housing and food and education crisis, our potential immigrant policies, and our seemingly ceaseless oppression of millions of non-whites. (But let’s not get started down that road…)

So what do we stand for? What does America represent? Just like the characters in these books and movies, our country is baffled by what it is. Perhaps America is like a teenager, lashing out and suffering what is hopefully just a growing pain. Or perhaps it’s like a middle-aged man going through a mid-life crisis, nostalgic for his past, jealous and wary of others that have emerged stronger than him, and confused and scared for how he got to where he is. Either way, it’s a crisis of identity. And that’s not something to be taken lightly.

So what do we stand for? What does America represent? Just like the characters in these books and movies, our country is baffled by what it is. Perhaps America is like a teenager, lashing out and suffering what is hopefully just a growing pain. Or perhaps it’s like a middle-aged man going through a mid-life crisis, nostalgic for his past, jealous and wary of others that have emerged stronger than him, and confused and scared for how he got to where he is. Either way, it’s a crisis of identity. And that’s not something to be taken lightly.

It would be impossible for me to weave these male artists together into a seamless cohesive narrative on our country (lest I wished to turn this blog into a small senior thesis) but they certainly all have one thing in common: A great American spirit, a grappling with masculinity and manhood, and an emergence of self-empowerment and identity. (Also, they’re all wonderfully intoxicating compositions in their own rights.) Without reducing these art forms into something extremely black-and-white, I would argue that all these artists transcended modern conventions and found power within their artistic vision; but underneath the surface all of them contain a darker history etched in their lines. And its this expression of darkness, to me, that makes mastery; that’s what makes art beautiful, and worth celebrating, and genuine depiction of identity, and American.

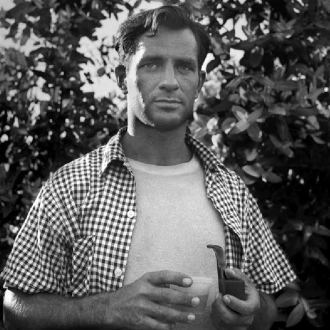

For example, on the surface, Stuart Davis and Jack Kerouac’s works contain an exuberance, a dramatic and excited display for the cultural and artistic offerings of America. In The Dharma Bums, Kerouac talks of “mad” young Americans hiking and meditating and drinking and orgy-ing away their life in the Cascades and Sierras. “Japhy was full of great ideas like that,” the narrator describes his friend’s talent for packing light. “What hope, what human energy, what truly American optimism was packed into that neat little frame of his!”

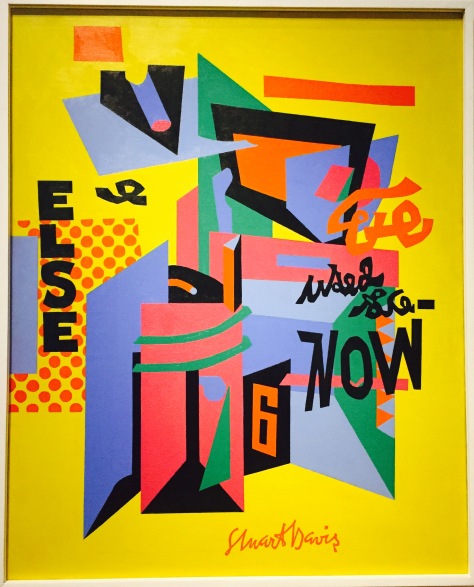

Truly American optimism. This is how we identify – liberated, optimistic, full of ideas and possibilities. Consider the art of Stuart Davis, whose aim was to be “distinctly American” in the “Whitman sense.” Davis – hugely influenced by the rise of jazz – depicts a bright, colorful, jubilant expression of American life. But the irony is that his art was inspired by predominantly African-American expressions, the products of those who had suffered and endured oppression solely based on their heritage, i.e. being non-white Americans.

The exhibition in the National Gallery didn’t point out all of the darkness that underlies this exuberant “American” art, but I’m not sure that’s what Stuart Davis himself was after, either. Holland Cotter from the NY Times touched on this in an article about the exhibit; he writes that some of Davis’ thinking about art seems “locked in the past”:

I’m thinking about the way he identified his art as American, a product of, and a homage to, “the wonderful place we live in,” a place of entrepreneurial appetites and Walt Whitman-esque enthusiasms. I’m thinking of his insistence that art’s primary moral role is, or should be, to add pleasure to the world, to give an illusion of ordering chaos, as opposed to facing it and staring it down.

Yes – the notion that art must concede with “American optimism” is outdated; rather, one of its primary moral roles is to illuminate the chaos, and identify with turbulence and suffering, if it is to capture an American spirit. The darkness is with us, among us. I keep coming back to this passage in Black Boy, Richard Wright’s autobiography, in which he describes feeling innately like an outsider as a young boy:

In shaking hands I was doing something that I was to do countless times in the years to come: acting in conformity with what others expected of me even though, by the very nature and form of my life, I did not and could not share their spirit…

(Whenever I thought of the essential bleakness of black life in America, I knew that Negroes had never been allowed to catch the full spirit of Western civilization, that they lived somehow in it but not of it.)

Negroes had never been allowed to catch the full spirit of Western civilization. What a bold, jarring statement. I would imagine most Blacks would agree with it. But either way I think that today, when we look at the overall American art forms from the past several centuries, the “Negro spirit” of Wright’s time is a huge, unavoidable component of the “modern” American spirit, even if we have to look between the lines.

For example, Jack Kerouac, a visionary of white-hipster Western America, rarely mentions African Americans in his novels (or at least, The Dharma Bums) more than once or twice. Under the surface, though, Kerouac was fascinated by – and even jealous of – the African American culture in his time. (“I walked on Welton Street wishing I was a ‘[n-word],’” Kerouac wrote in his journals in Denver of 1949, “because I saw that the best of the ‘white world’ had to offer was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night.”) You wouldn’t find this spirit much in his novels, but it’s certainly there in his personal writings published in 2004. When Kerouac looked at the problems in American culture (consumerism, obsession with entertainment and money etc), he actually found a sense of salvation in the non-white world. Consider this passage from his visit to Poughkeepsie in 1949:

and even jealous of – the African American culture in his time. (“I walked on Welton Street wishing I was a ‘[n-word],’” Kerouac wrote in his journals in Denver of 1949, “because I saw that the best of the ‘white world’ had to offer was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night.”) You wouldn’t find this spirit much in his novels, but it’s certainly there in his personal writings published in 2004. When Kerouac looked at the problems in American culture (consumerism, obsession with entertainment and money etc), he actually found a sense of salvation in the non-white world. Consider this passage from his visit to Poughkeepsie in 1949:

What dismal streets… what dismal lives… what futurelessness & hapless woe. Thousands of drunkards in bars. But out of this wreckage rises a Cleo – a veritable Cleophus – the “Negro Neal” I met there this weekend – actually a “Negro Allen” in substance…

The future of America lies in the spirituality and strength of a Negro like Cleo… I know it now… and in all those who understand and receive him. It is simplicity and raw strength, rising out of the American ground, that will save us. We will be saved… There are great undiscovered peoples in America… Our class-laws will collapse.. otherwise America will collapse… and America will not collapse. You feel it in the busy streets… the swing of things; the sound of things going on, going up …

It’s amazing to me, how relevant this passage feels almost seventy years later. The swings and sounds – he’s certainly referring at least in part to the sounds of jazz rising from the streets and clubs, from mostly African American artists. It will save us. This “raw strength” rising from “undiscovered peoples” is the epitome of the triumphant American spirit, and is what will prevent us from destruction; and our future lies in all those who understand and receive this spirit and strength.

This is where “Moonlight” comes in. The movie was created by and based on the true life of Tarell Alvin McCraney, a gay black man who grew up in a Miami ghetto. Despite his turbulent and dangerous upbringing, his strength, spirit, choices and perhaps some chance prompted him to do and create many great things, including this recent beautiful film about power, identity, and ultimately love’s triumphs. There is no doubt that it achieves a level of greatness. But McCraney, as quoted in the LA Times, expressed nervousness about being labeled as just a “queer love story” or a “well-done black movie.”:

The thing that scares me is that people will try to use that to put it in this corner, because we can’t consider it ‘a great story.’ We have to consider it ‘this kind of great story.’ There is no part of me that wants to shirk this identity — it’s just who I am, how I got here.

And there’s no part of me that wants to shirk this American identity – that this is who we are, this is how we got here. Avoiding our past will only cause more pain. I can’t change our past, or what America has stood for. But I can change the way I look at everything created here, and understand the darknesses amidst the exuberance, and understand that these heavier stories deserve the status of greatness, and deserve to be OF the American spirit. While I can enjoy the fun elements of American art – be it Stuart Davis’ paintings, or Jack Kerouac’s ramblings of enlightened hitchhikers – I don’t want to take them on surface level; I want to understand how they actually fit into this country’s identity. In times like this, where I feel slightly lost in my own turf, it is consoling, necessary even, to seek our history, to peer into the masteries of American art, to find a common ground.

p.s. some more moon quotes:

From The Dharma Bums:

“But night would come and with it the mountain moon and the lake would be moon-laned and I’d go out and sit in the grass and meditate facing west, wishing there were a Personal God in all this impersonal matter. I’d go out to my snowfield and dig out my jar of purple Jello and look at the white moon through it. I could feel the world rolling toward the moon… bucks with wide antlers, does, and cute little fawns looking like otherworldly mammals on another planet with all that moonlight rock behind them.

…One night in a meditation vision Avalokitesvara the Hearer and Answerer of Prayer said to me “You are empowered to remind people that they are utterly free.”

——-

From http://www.vulture.com/2016/11/tarell-alvin-mccraney-on-writing-moonlight.html

Tarell Alvin McCraney: I struggle with the person I’ve created to present to the world versus my authentic self. And to me, that’s one of the things this [movie] illustrates. It’s not the only thing for sure, but it illustrates who we become in order to survive, or what we think is surviving, and the cost of that.

Vulture: And also, the joy of when you feel like someone can see you for who you are.

McCraney: Absolutely. Being seen is so important and when someone sees you through all of your bullshit or through all of your performances, good or bad … I think in some places, that little boy had to perform certain ways. He was in danger; his world was chaos. But at every avenue, Kevin was there like, I see who you are, I can see you. To me that’s why Moonlight, the title, makes so much sense. To be seen under this light, it’s like it doesn’t matter that it’s just a reflection of the sun. To be seen period is enough. It’s beautiful and it doesn’t matter that it’s in the dark. It doesn’t matter that everything else around you is dark. If you get that light on you, to bask in it, it may not be as warm as the sun, but it’s certainly feels so good.”

—